Zak Lylak

Author of fiction

Zak's Movie Stack

I like a variety of films, but those I connect with most are usually brutally honest, stripping away existential salves, which for many of us are disingenuous and nauseating. Such unveilings hang Pollyanna in the gibbets, displaying the truthful horror of a world infested with plastic escapism, and 'belief in belief', unaware of its irrational self-deprecation; a culture that rejects the natural for the fake. This disgust with 'Life' is understandable, yet claims to be its opposite. Revelation of 'truth' acts as a conduit for a strange kind of love that meets itself in the darkest moments, and for 'truth' to be truly true, it must be incomprehensible at its core. So, there's always room for humour, creative mischief, and the surreal.

For me, the films listed act less as a mirror, and more as a sledgehammer to demolish the ontological advertising hoarding that has been erected all around us. What might seem like a taste for bleakness is really a distrust of false consolation which is often more violent than despair itself. There's no comfort here, but by refusing to lie about its structure, pain can be witnessed and allowed space to breathe. The films don’t say everything's gonna be alright, they confirm that you’re not defective if you feel the fracture between the song and the nature of the instrument used to create it.

Perhaps I'll make a film some day, who knows? In the meantime, my favourite movies are below (I prefer the term 'films' over 'movies', but for the sake of variance). In no particular order, and subject to change:

Donnie Darko — Richard Kelly (2001)

Balancing teenage malaise with metaphysical dread, Donnie Darko treats suburbia as a fragile stage set propped up by denial and vapid motivational slogans. Its philosophy is less about answers than about the anxiety of asking the wrong questions too early, filtering existential terror through darkly comic detachment. Kelly uses eerily precise compositions, an anachronistic pop soundtrack, and a constant sense of something slightly out of joint. The result is a worldview where causality feels optional and fate vaguely sarcastic. Cruel humour mirrors the sick joke of existence, but its sharp precision undercuts authority figures and disingenuous, life-affirming platitudes. There's no salvation, but a quiet decision to care despite cosmic indifference. The ultimate rebellion is upending fate through a love expressed in quiet sacrifice, one the world will never know.

Canticle of All Creatures — Miguel Gomes (2006)

This playful short film treats spiritual reverence with a wink and a sigh, folding centuries together as though time itself were merely another costume. Gomes approaches faith not as dogma but as performance; sung, reenacted, misremembered, and gently mocked. The film’s modest, deliberately artificial style allows sacred history and present-day wandering to coexist without hierarchy, suggesting that belief survives less through certainty than through repetition and joy. Beneath its humour lies a quietly pessimistic observation: devotion, even to the natural world, carries the seeds of possessiveness. Nature itself is portrayed as absurdly fake, and mechanistic. Yet Gomes lets irony and affection share the same frame, reflecting the broken mirror of perception.

Luz: The Flower of Evil — Juan Diego Escobar Alzate (2019)

Operating somewhere between myth, fever dream, and philosophical provocation, Luz: The Flower of Evil examines morality, exposing it as something inherited, not chosen. Its stark, theatrical compositions, and deliberate pacing, evoke a world governed by archetypes. Good and evil are exposed as little more than ancestral burdens. The film’s pessimism is uncompromising. Innocence is a fragile delusion, and nature is indifferent to the tribulations of human existence. Ritualized movement, exaggerated symbolism, and playful curiosity, introduce a dark humour that keeps the experience from collapsing into solemnity. Belief carries the flavour of beauty, despite the reality of its cruel poison.

The Innocents — Eskil Vogt (2021)

Vogt’s film quietly dismantles the comforting myth that childhood equals moral purity. Set against sunlit apartment blocks and ordinary playgrounds, it explores how power reveals rather than corrupts, using restraint instead of spectacle to unsettling effect. The philosophy here is bleak but precise; empathy is not ubiquitously innate, cruel power may take its place. Using static frames, naturalistic performances, and an absence of overt explanation, forces the viewer into an uncomfortable complicity; the harm unfolds without narrative cushioning. The gap between adult assumptions and children’s inner worlds exposes the fiction of human goodness.

Radiance — Naomi Kawase (2017)

Radiance approaches perception as both gift and burden, asking what it means to truly see when sight itself is unstable. Kawase’s gently pessimistic philosophy treats impermanence both as tragedy, and a fundamental condition of intimacy. Her camera lingers on faces, textures, and fading light, turning sensory attention into sympathy. Narrative tensions arise less from conflict than from the misalignment of words and images, intention and reception. There's a soft, almost mischievous irony in how carefully the film dismantles the authority of vision, reminding us that clarity often arrives after something begins to disappear. Our perception is fragile, temporary, and precious, yet often acts as a veil that hides a deeper truth.

The Booth at the End — Jessica Landaw (2010)

Stripped almost entirely of spectacle, The Booth at the End was initially released as a series, but later stitched together as a film. Staged moral inquiries unfold as whispered confessions over coffee. Fulfilment of desire is framed as a transaction, and ethics as something easily postponed. It presents the world with brutal realism; a place where deeper meaning is a mask, easily discarded for kicks. Locked-down frames, repetitive spaces, and an almost monastic refusal of visual variety, turns conversation into the primary arena of tension. There’s a bleak, dry humour in how calmly the lens observes the ease of human compromise. Its pessimism isn’t theatrical but procedural, suggesting that belief, responsibility, and guilt don’t arrive with thunder, but are quiet processes, easily eclipsed by the temporary delight. Decisions aren't hurried, and there's plenty of time to reconsider, but no one ever quite does.

Still the Water — Naomi Kawase (2014)

Kawase’s early work already carries her signature fascination with impermanence, here rendered through a quiet dialogue between grief and landscape. Still the Sea treats the ocean not as metaphor but as presence; vast, patient, and indifferent to human urgency. The film’s philosophy resists narrative consolation, allowing emotion to surface in gestures, silences, and the slow accumulation of ordinary moments. Kawase’s handheld intimacy creates a sense of fragile proximity, as though the camera itself were unsure how long it's allowed to stay. Gentle pessimism, tempered by compassion, presents loss in a way that's neither resolved nor aestheticized, only absorbed. Meaning dissolves, only being remains.

Attenberg — Athina Rachel Tsangari (2010)

Attenberg approaches human behaviour with the curiosity of a nature documentary and the mischief of a private joke. Tsangari frames social interaction as something alien, learned through observation rather than instinct. Intimacy is awkward by design, an evolutionary glitch we persist in reenacting. Stylized movement, deadpan delivery, and playful disruptions of realism create an aesthetic that oscillates between tenderness and satire. Dark humour slips in through repetition and exaggeration, mocking the rituals of adulthood, and exposing their insanity. Beneath its surface oddity is a sincere meditation on mortality and inheritance, where learning how to live feels inseparable from learning how to say goodbye. Intended or otherwise, the daring presentation of a neurodivergent ontology left me screaming for an encore.

Nothing Really Happens — Justin Petty (2017)

This small, sharply observed film leans into stasis as a philosophical position rather than a narrative problem. Nothing Really Happens examines emotional inertia with a wry, almost apologetic humour, finding quiet despair in routines that resist disruption. For a cohesive minimalist approach, Petty makes use of unadorned spaces, understated performances, and an almost stubborn refusal of dramatic escalation. We see a worldview where change is theoretically possible, but practically exhausting. The pessimism here is subtle and familiar. A tragic, inevitable drift. The pain comes from an authentic awareness stripped of agency; a failure to die inside. With comedic absurdity, the film takes its own stillness exceptionally seriously, intermittently bursting into surreal horror. The audience is dared to conjure meaning where none exists. In that attention, a vague form approaches. At times, it appears to be a flicker of hope, but it's the shadow of our own denial. A terribly underappreciated masterpiece.

The Brave — Johnny Depp (1997)

The Brave just managed to beat off Dead Man as the lone Depp film I included in this list. It carries the weight of a modern gnostic parable, presenting a world where material survival and spiritual annihilation appear deeply entwined. Depp’s direction frames existence as a fallen state; harsh, transactional, and ruled by unseen powers that trade suffering for sustenance. The desert setting becomes more than backdrop; it's a stripped-down cosmos where illusions fall away and knowledge arrives at a terrible price. There’s a solemn, almost ascetic visual language at work, punctuated by moments of bleak irony that underscore how little agency remains once the terms are set, not that there was any beforehand.

Despite making the ultimate sacrifice, all that's gained is a ramshackle, dysfunctional, short-lived fairground; a parable of contemporary 'progress'. There's a strong whiff of blood lurking from the genocide the USA was built on, and brazen exposure of the pathological cruelty of obscene capitalism. Littered with iconic and astrological symbolism, there's a distinct undercurrent of occult ritual. The film’s pessimism is profound but purposeful, suggesting that awakening in a corrupted world may offer clarity without mercy. And if transcendence exists, it demands everything.

Dancer in the Dark — Lars von Trier (2000)

A tearjerker that becomes more harrowing each time I view it. Von Trier’s bleak musical is built on a cruel contradiction: the more exuberantly it sings, the more merciless its world becomes. Dancer in the Dark treats optimism as a fragile, almost defiant hallucination, staging fantasy not as escape but as resistance. The film’s philosophy is brutally real; systems crush individuals with mechanical indifference. However, it grants imagination a strange moral purity.

Handheld camerawork and harsh digital textures anchor the film in bodily reality, making the musical interludes feel like private acts of revelation. The secret knowledge of music shielding the soul from a hellish life where honesty and innocence are abused and deprived. Dark humour flickers in the gap between sincerity and absurdity, but never softens the blows. Joy exists only as long as one dares to invent it, but eventually, that capacity is stolen, too.

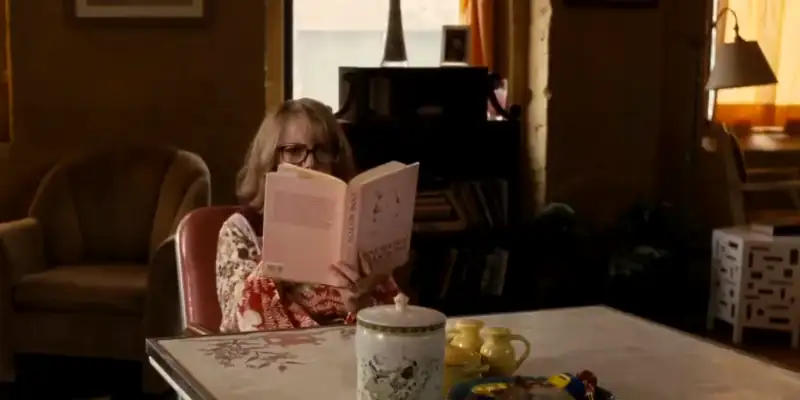

The Planters — Alexandra Kotcheff & Hannah Leder (2019)

The Planters is an adorably quirky film that conjures magic without brushing the darker side of life under the carpet. It also made me laugh; belly laughs. Set in a sun-bleached nowhere that feels gently out of time, the film approaches sustenance as something buried, misplaced, and rediscovered by accident. In its isolated setting, genuine human connection is rare, fragile, and frequently misunderstood. Cruel realism is softened by playful humour and a deep affection for human oddness. The film’s handmade aesthetic and deliberate artificiality suggest a world assembled rather than inherited, where sincerity survives through whimsy. In this desert of mild miracles, a golden nihilism emerges where melancholy and delight coexist.

The Bothersome Man — Jens Lien (2006)

Jens Lien’s deadpan fable presents a world where comfort has replaced meaning, and dissatisfaction has been carefully engineered out of existence. The Bothersome Man unfolds like a bureaucratic afterlife stripped of transcendence, its immaculate surfaces concealing a spiritual vacuum. Stark compositions and controlled performances reinforce a sense of existential quarantine, while the film’s dry humour sharpens its critique rather than relieving it. Once the protagonist, Andreas, escapes the sterile, unfeeling world he feels imprisoned in, he finds things even worse. Each time he tries to live his life, or afterlife, with authentic passion, he's forced into a more severe state of alienation.

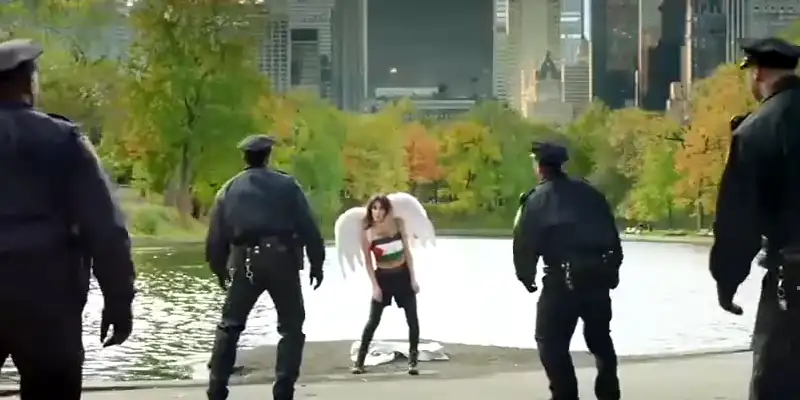

It Must Be Heaven — Elia Suleiman (2019)

An essential watch for anybody who holds regressive views of what life in Palestine was like, before its recent demolition. Suleiman’s quietly mischievous film drifts through the modern world like a bemused philosopher observing a cosmic practical joke. It Must Be Heaven treats national identity, exile, and belonging, with minimalist wit. The nature of alienation is revealed through hostile indifference; there's much here that resonates with The Bothersome Man. The film’s near-silent protagonist becomes a gnostic observer, witnessing a reality governed by invisible absurdities and ritualized violence. Carefully composed tableaux transform everyday life into gentle satire, where humour emerges from stillness rather than punchlines. Beneath the playfulness lies the melancholic acceptance that paradise is always elsewhere. Zen-like rebellion arises from a refusal to stop finding the world strange and incomprehensible.

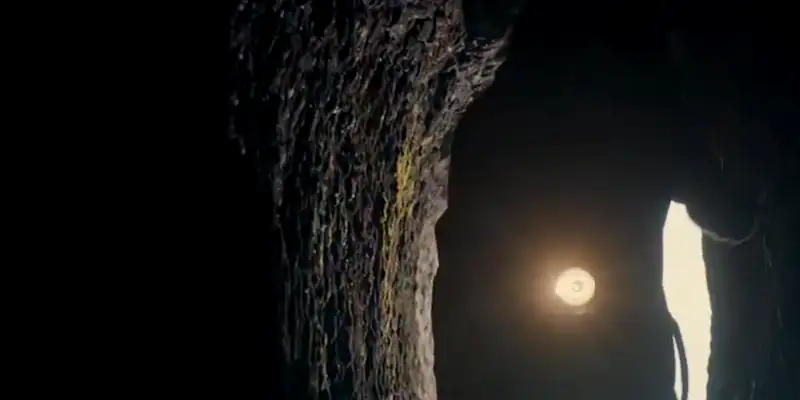

Mirtillo: Numerus IX — Desiderio Sanzi (2025)

Mirtillo: Numerus IX unfolds with the intensity of an intimate theatrical rite, as though the viewer has been invited into a sealed chamber rather than a cinematic space. Sanzi leans fully into austerity, allowing performance, voice, and symbolic gesture to carry the weight of meaning. The film’s gnostic sensibility is palpable: the world presented feels constructed, restrictive, and faintly hostile, while knowledge emerges through endurance rather than revelation. Its minimal staging and deliberate pacing emphasize presence over illusion, blurring the line between actor and witness. There's little comfort offered, but a quiet respect for attention itself, as if sustained observation were a form of devotion. Any humour is dry and subterranean, surfacing only in the tension between solemnity and artifice, reinforcing the sense that truth, if it exists, is something enacted rather than explained.

Repo Man — Alex Cox (1984)

Repo Man hurtles through Reagan-era America like a transcendent punk gospel, insisting that reality is unstable, authority illegitimate, and meaning best approached sideways. Cox fuses anarchic humour with cosmic paranoia, presenting a world where consumerism feels like a false god and alienation is simply baseline existence. The film’s scrappy aesthetic, harsh lighting, abrupt edits, and an aggressively present soundtrack, mirrors its philosophy; coherence is overrated. Beneath the playfulness lies the bleak insight that structures of power are both absurd and absolute. Knowledge arrives not through enlightenment, but through accident, curiosity, and refusal. The joke, ultimately, is that transcendence might exist, but it looks suspiciously like trash glowing in the trunk of a car.

Memoria — Apichatpong Weerasethakul (2021)

Memoria listens more than it speaks, unfolding as a meditation on perception, time, and the quiet terror of displaced experience. Weerasethakul treats memory as a porous boundary rather than a personal possession, allowing sound and silence to guide the film’s philosophical undertow. Its austerity is gentle but exacting, asking the viewer to slow down to the pace of attention itself. There's a gnostic undercurrent in the suggestion that reality contains hidden frequencies, perceptible only to those willing, or condemned, to listen. Narrative dissolves into sensation, and being becomes something felt rather than resolved. The film’s calm surface carries an existential unease, proposing that awareness is both a gift and a burden, and that remembering may be inseparable from becoming unmoored.

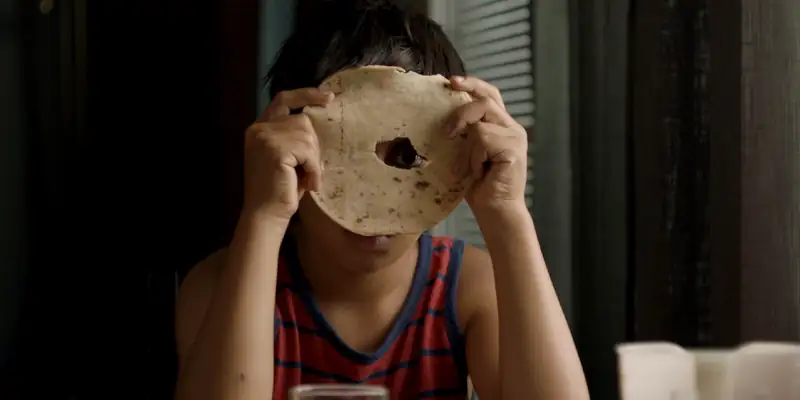

Fukuchan of Fukufuku Flats — Yōsuke Fujita (2014)

This quietly eccentric film approaches marginality with a mix of warmth, melancholy, and understated absurdity. Fukuchan of Fukufuku Flats treats social invisibility not as tragedy but as a lived condition shaped by routine and resignation. Fujita’s philosophy is gently pessimistic: happiness appears fleeting, often imagined, and rarely aligned with social expectations. The film’s modest, almost handmade aesthetic mirrors its characters’ tentative hopes, allowing humour to arise from awkward pauses and small misalignments rather than punchlines. There’s a tender irony in how sincerity struggles to survive in a world that rewards performative normalcy. Meaning here is fragile and provisional, found less in transformation than in endurance, and in the quiet solidarity of those who remain slightly out of place.

Mulholland Drive — David Lynch (2001)

Mulholland Drive operates like a shattered mirror, reflecting desire, identity, and illusion in fragments that refuse to reassemble neatly. Lynch’s philosophy is mercilessly pessimistic: the self is unstable, dreams are traps, and Hollywood functions as both factory and mythological machine. The audience is seduced and disoriented by velvet darkness, saturated light, and haunting sound, reinforcing the sense of a world governed by false narratives. Gnostic echoes emerge in the idea of a corrupted reality, where truth exists, but remains obscured by performance and fantasy. Dark humour flickers in the exaggeration of archetypes, yet the laughter never lingers. When dream collapses, reality offers no comfort.

Requiem for a Dream — Darren Aronofsky (2000)

Aronofsky’s relentless film treats desire as a mechanical process, stripping aspiration of romance and revealing its brutal momentum. Requiem for a Dream presents a universe where hope is easily manufactured and mercilessly exploited. The aggressive editing, repetitive visual motifs, and invasive sound design create an aesthetic of entrapment, mirroring cycles that tighten rather than progress. There's a cruel irony in how the characters’ dreams remain vivid even as their bodies and agency erode. The film offers no transcendence, only an accumulation of need, damage, and silence. Fate defines characters by what disappears, and what fills the gaps, when desire is allowed to operate unchecked.

Pasture — Sean Hardaway (2021)

Pasture unfolds like a psychological enclosure, less interested in shock than in the slow erosion of certainty. Hardaway’s film pulls you into the experience of paranoia, where care and control become indistinguishable: is this heroic salvation or demonic gaslighting? The austerity of its rural setting and controlled visual language make clear that isolation is not an accident but a method. Easy metaphors are absent, leaving a lingering ambiguity, allowing unease to accumulate through repetition and restraint. There's a faint, cruel irony in how gestures of help mask deeper violations, suggesting a world where perception is imposed and truth manufactured. Any hope offered is provisional at best, fragile enough to dissolve, the moment one insists on clarity.

Lemon — Janicza Bravo (2017)

Lemon approaches emotional emptiness with a scalpel disguised as a joke, carving out a portrait of privilege so insulated it barely registers its own decay. Life in this world is acerbic and quietly merciless. Self-awareness does not guarantee transformation, and irony often serves as a comforting blanket. A stripped-down aesthetic combine with deliberately awkward rhythms to heighten the sense of social alienation. Discomfort is the primary language, and humour arrives dry and sideways. Beneath the playfulness lies a pessimistic observation that intimacy, without humility, curdles. Authentic being glimmers through the cracks, but is crowded out by entitlement, distraction, and the refusal to sit still long enough to feel anything fully.

The Lobster — Yorgos Lanthimos (2015)

Lanthimos constructs a world where love has been bureaucratized, and loneliness treated as a moral failure requiring correction. The Lobster blends deadpan absurdity with existential cruelty, presenting social ritual as a form of quiet violence. Individuality survives only through compromise, and authenticity that tries to assert itself is extinguished quickly. Systems designed to eliminate suffering merely reorganize it; suffering is interchangeable but inescapable. The film’s rigid compositions and affectless performances create a sense of emotional quarantine. Dark humour sharpens the critique. The perception of a false world governed by arbitrary rules, where escape demands either conformity or self-erasure, mirrors existential gnosis.

Mad God — Phil Tippett (2022)

Mad God feels less like a film than an excavation, dragging the viewer through a handcrafted underworld of mechanistic rot and violence, such is creation. Tippett’s decades-long project channels a profound pessimism: the world is broken at its foundation, ruled by indifferent forces, and sustained through endless cycles of pain and destruction. Narrative dissolves into process, replaced by ritualized labour and grotesque transformation. The stop-motion aesthetic, tactile and punishingly detailed, reinforces the sense that matter itself is a curse. Any humour is black as pitch, emerging from the deluge of suffering and effort. Transcendence exists only through insight, not transformation.

Import/Export — Ulrich Seidl (2007)

Seidl’s stark, unsentimental film treats globalization as a spiritual vacuum, where movement promises opportunity, but delivers only new forms of alienation. Import/Export embraces a dogged realism, refusing narrative symmetry or emotional release. Its austere, observational style exposes bodies at work, at rest, and at their most vulnerable, implicating economic systems in intimate degradation. The film’s humour is minimal and deeply uncomfortable, surfacing in moments where routine collides with quiet despair. Seidl offers no moral framing, only labour, exhaustion, and unmet desire. A hard-hitting portrayal of how easily human dignity is translated, traded, and diminished across borders that promise everything and explain nothing.

Midsommar — Ari Aster (2019)

Midsommar replaces darkness with relentless daylight, exposing emotional vulnerability under the guise of pastoral serenity. The journey into the land of the midnight sun, embracing constant light, is punctuated by inversion; a nod toward the occult philosophy of 'as above so below'. In the bleak pragmatism of the cult, suffering does not disappear but is absorbed, redirected, and given structure. The film’s meticulous symmetry and folkloric pageantry suggest a world where meaning is manufactured through participation rather than belief. Outsiders are assessed for depth, intuition, and potential. Failures are disposable, executed in artistic ritual with twisted humour.

The initiate's trauma is mocked through psychopathic mirroring; her pain and emotion reflected as a performative act resembling the sacrificial masks of Ancient Phoenicia. Humanity is destroyed in routines of indoctrination. Care is cremated, and submission becomes the sole option for reconfiguration. Inside this closed system, clarity is bought at the cost of autonomy; ethics do not apply to individuals, but to the perpetuity of the system. Transcendence is available, but only if one is willing to surrender idealism to the pragmatism of something as horrifyingly indifferent as the mechanistic cycles of nature; a collective psychopathic cosmology arising through despair, disease, bereavement, trauma, blame, and conflagration. An uncanny foretelling of the 2020s.

Naked Lunch — David Cronenberg (1991)

Cronenberg’s hallucinatory adaptation treats creativity as infection, and identity as something endlessly rewritten. Naked Lunch operates in a gnostic nightmare where reality fractures under the pressure of language, addiction, and desire. The film’s grotesque organic machinery blurs boundaries between body, text, and control, suggesting that authorship itself may be parasitic. Cronenberg’s cool, clinical tone heightens the absurdity, allowing dark humour to emerge from repetition and escalation rather than punchlines. Meaning is never stable, only rearranged, as if truth were encoded and deliberately mistranslated. The result is a philosophy of contamination: knowledge spreads through exposure, not enlightenment, and the price of insight is permanent disorientation. To live without anxious dissonance requires one to embrace insanity.

Antichrist — Lars von Trier (2009)

Antichrist descends into grief, not as an emotion to be processed, but as a force that reorganizes reality itself. Von Trier frames nature as hostile, sentient, and faintly accusatory, rejecting any comforting distinction between inner turmoil and external world. The film’s ontology is severe: creation is corrupt, knowledge breeds despair, and suffering is not redemptive. Stark visual beauty collides with brutality, producing an aesthetic that feels both ritualistic and confrontational. Cruel humour surfaces in the excess of symbolism and the film’s refusal to soften its metaphysical claims. Enlightenment is exposure, garments of delusion stripped through pain, silence, and the collapse of inherited moral frameworks.

Inland Empire — David Lynch (2006)

Inland Empire unravels identity with patient cruelty, abandoning narrative coherence in favor of recursive dread. Lynch treats cinema itself as a haunted apparatus, where roles, memories, and selves bleed into one another. The film’s digital harshness strips away illusion, replacing dreamlike polish with chafing rawness. Gnostic anxieties permeate its structure. Reality appears layered, artificial, and governed by unseen rules that punish awareness. Dark humour flickers in dislocation with moments that feel almost comic until they strip amusement with recurrence. Meaning is neither revealed nor resolved, only deferred, as the film insists that understanding may be indistinguishable from being trapped inside the machinery that produces it. An existential nausea that vomits the message of eternity as a psychedelic nightmare.

Pan’s Labyrinth — Guillermo del Toro (2006)

Del Toro’s dark fairy tale situates imagination as both refuge and indictment, refusing to separate fantasy from historical brutality. Pan’s Labyrinth embraces a tragic truth: innocence does not protect against violence, and wicked obedience often masquerades as virtue. The film’s richly tactile fantasy world contrasts sharply with its stark political reality. Two systems of authority are present, one mythic, one fascist. Both demand sacrifice. The 'real' world is governed by cruelty. Secret knowledge offers temporary escape, but not bodily survival. The film’s beauty is sincere yet mournful, proposing that transcendence may arrive only through total surrender of the material world. By contrast, order and control of the physical, through homogenized culture, requires forfeiture of the soul.

One Point O — Jeff Renfroe & Marteinn Thorsson (2004)

One Point O, also known as Paranoia: 1.0, presents reality as a system already compromised, where technology does not invade human life so much as complete it. The film’s keen pessimism is quietly total: the world is artificial, the body porous, and autonomy largely ceremonial. Scenery is infused with paranoid austerity, as if existence itself were being beta-tested. Narrative unfolds less through causality than through accumulation, reinforcing the sense of an unseen logic tightening its grip. Dark humour surfaces in the banality of surveillance and control, suggesting that domination no longer needs villains, only infrastructure. Being is fragmentary and unstable, accessible only through glitches, absences, and the uncomfortable realization that awareness may arrive too late to matter.

Female Perversions — Susan Streitfeld (1996)

This sharp, unsettling film interrogates identity as something performed under pressure, particularly within structures that reward control while punishing vulnerability. Female Perversions approaches desire and ambition with a cool, almost surgical cynicism, exposing how empowerment can easily mutate into self-surveillance. Streitfeld’s stylized compositions and heightened theatricality reflect a world where interior life is constantly being translated into acceptable form. There’s a dark, ironic humour in how transgression is permitted only when it reinforces the very systems it appears to resist. The film resists moral clarity, instead suggesting that liberation and constraint often share the same architecture. Self is fractured and reassembled on the fly, moment by moment, in the uneasy space between authenticity and survival.

The Zero Theorem — Terry Gilliam (2013)

Gilliam’s dystopian fable treats meaning as an administrative problem, endlessly deferred by bureaucracy and spectacle. The Zero Theorem embraces a fatalism, presenting a universe where cosmic purpose is promised, but perpetually withheld. Its maximalist aesthetic of clashing colours, oppressive design, and visual excess, creates a sense of suffocating artificiality; a world was built to distract from its own emptiness. Life is a superficial bubble of noise and consumption, while truth remains inaccessible, perhaps nonexistent. Dark humour thrives in cyclical iterations of absurd logic loops; escapism from the metaphysical discourse that could result in only one conclusion—the inquiry is futile. Meaning is derived only from the obsessive pursuit, rather than face the revelation that there's none.

Don’t Look Deeper — Catherine Hardwicke (2022)

This compact, uneasy series (stitched into a movie) treats selfhood as a manufactured interface rather than an innate truth. Don’t Look Deeper draws from gnostic sci-fi traditions, suggesting a world where creation is careless and knowledge destabilizing. Depth of being, empathy, and reflexive anxiety, are not exclusive to humans, many of whom lack all three. Uncanny rupture pierces suburban normalcy, grounding philosophical concerns in the emotional immediacy of prejudicial dogma and associated threats to survival.

Angst emerges not through catastrophe but from design. Identity and existence are fundamentally disposable; installed, monitored, revised, and shut down. Therapy, a tool for debugging a machine. An unsettling mirror is held up to contemporary pressures of conformity, exemplified by hegemonic beauty standards demanding the body be moulded to a generic ideal; a soulless, cyborgian sexification. There’s muted irony in how rebellion itself feels anticipated, absorbed into the system’s expectations. Enhanced awareness becomes less an awakening than an irreversible loss of innocence; nothing exists outside the simulation.

Streaker — Peter Luisi (2017)

Streaker wraps existential despair in farce, using scandal and spectacle to expose the emptiness of modern ambition. Luisi’s satire treats capitalism as a game whose rules are absurd but ruthlessly enforced, where morality bends easily under the promise of attention. The film’s bright, exaggerated tone, masks a desolate culture where value is manufactured through visibility, and dignity is negotiable. Humour functions as both weapon and anesthetic, inviting laughter even as it implicates the viewer in the same transactional logic. Beneath the playfulness lies a bleak clarity—freedom is permitted, even encouraged, so long as it remains profitable. Meaning survives only as branding; a shiny wrapping on an empty box.

Brazil — Terry Gilliam (1985)

Brazil imagines bureaucracy as a total cosmology, a self-sustaining system where error is sacred and imagination subversive. Gilliam’s Orwellian vision is seductively exuberant, yet simultaneously suffocating. The film treats fantasy not as escape, but as the last unregulated space left to the psyche. However, reality itself is a phantasm, administered by false authorities; its nature unveiled only in dreams, paperwork errors, and sabotage. Dark humour flourishes through exaggeration and sheer audacity, yet the laughter never dispels the dread. Individuality is actively hunted, corrected, and erased. Transcendence, if achieved, comes only by withdrawal from the system, adopting decoherence, and exiting life as officially defined. However, the death of public identity and transgression that follows appear to have been part of the master plan.

Dune — David Lynch (1984)

Lynch’s Dune treats prophecy, power, and perception as overlapping hallucinations, staging a universe where destiny is both unavoidable and deeply suspect. The gift of messianic knowledge is a curse, obtained through an awakening capable of killing the seeker. Inner voices, whispered futures, and hyperbolic ritual suggest a gnostic cosmos of information unbound by time. However, the motive of competing ethnic factions remains base despite being framed as sacred: dominant power and resource acquisition.

Beyond the spectacle of a weirdness that is both monstrous and enchanting, morality and meaning dissolve in the shadows. Dense sound design, and oppressive visual scale, create a sense of psychic saturation, as though thought itself were under siege. Ascended consciousness is a sensed connection, not a rational cogitation. Humour is strange and unsteady, embedded in excess, and solemnity pushed just beyond plausibility. Enlightenment here is a dangerous burden, and the cost of seeing clearly may be the loss of ordinary human values. Forget the remakes, they're way off the mark.

eXistenZ — David Cronenberg (1999)

eXistenZ collapses the boundary between body and system, proposing reality as something plugged into, rather than inhabited. Cronenberg’s cool pessimism treats agency as an illusion maintained by interface design. Organic technology and fleshy apparatuses render the world disgustingly tactile and untrustworthy, reinforcing the sense of a gnostic trap where creators are careless and rules mutable. The film’s deadpan humour thrives in messy, spontaneous emergence, making confusion itself a recurring joke. Surety is endlessly deferred, nested within simulations that replicate doubt more efficiently than truth. Awareness offers no escape, only another layer of game play, suggesting that the most harrowing revelation may be not deception but inescapable participation in the horrors of biological competition.

Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter — David Zellner (2014)

This quietly devastating film treats belief as a survival strategy pushed past its breaking point. Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter approaches obsession with austere tenderness, refusing irony even as it documents a tragic misalignment between inner myth and external reality. The film’s conclusion is gentle but absolute: the world does not bend to belief, no matter how sincerely held. Snowbound landscapes and minimalist framing reinforce a sense of existential exposure, as though faith itself were wandering without shelter. There's a bleak, cosmic humour in the warm, indifferent assistance Kumiko is given to pursue her delusion, though it never tips into mockery. Meaning here is intensely personal, and catastrophically incompatible with the world tasked with receiving it. However, there's something profoundly magical about a paradoxical will that fundamentally rejects the reality that birthed it. There's an unsettling conclusion: there's divinity in a short life lived in the sovereign freedom of fantasy. The real tragedy was avoided: a slow death in mundane subjugation.

Mio on the Shore — Ryutaro Nakagawa (2019)

Mio on the Shore captures being as a suspended state, where desire and identity drift without resolution. Nakagawa’s adaptation embraces emotional austerity, allowing stillness and silence to carry the weight of unarticulated longing. Connection is tentative, often misunderstood, and shaped as much by absence as presence. Its soft, coastal imagery contrasts with aging, functional infrastructure, yet there's resonant, sentimental beauty in both. Any humour is minimal and incidental, emerging from awkwardness rather than intention. The transformative arc unfolds slowly, not as revelation but as gradual acceptance of the continual erosion of certainty; life as a process that replaces through destructive decay.

The Holy Mountain — Alejandro Jodorowsky (1973)

The Holy Mountain stages enlightenment as spectacle, provocation, and deliberate fraud, daring the viewer to mistake symbolism for salvation. Jodorowsky’s film is aggressively gnostic, presenting a world ruled by false idols, commodified spirituality, and grotesque rituals masquerading as wisdom. An excess of vapid meaning is piled into a repulsive mound, revealing the hidden taboo of that which cannot be named. Dark humour and playful blasphemy function as purifying agents, ridiculing authority even as the film attempts to construct its own. The ultimate pessimism lies in the revelation that transcendence cannot be consumed, followed, or filmed. Truth, if it exists, demands the destruction of illusion, including the mirage of the movie.

Clara — Akash Sherman (2018)

Clara treats the sincere search for cosmic meaning as isolating. Deep connection is rejected for the spiny carapace of intellectual formality, or through the relationship tourism of perpetual roaming. Both methods avoid the vulnerability of love; something life's cold, destructive forces always tear to shreds. Irony seeps in when the transcendence of mutual embrace appears most vividly through loss and obsession. The outcome is a synthesis of magic and science that appears to comfort, yet retains a galactic chasm that forsakes absolute union for future longing, and true revelation to a post-mortem world. Contemporary salvation sold by rebranding shabby religious dogma.

Synecdoche, New York — Charlie Kaufman (2008)

Kaufman’s monumental work treats sentience as an endlessly recursive trap. Self-awareness, akin to self-flagellation. Synecdoche, New York embraces a devastating premise: the drive to understand life, in order to fulfil desire, guarantees failure, as does the attempt to fulfil desire without understanding. When success seems within reach, corrupt biology and conflicting interests morph it into a mocking demon. The film’s collapsing layers of performance, memory, and simulation create a gnostic labyrinth where reality is replaced by increasingly distorted approximations. Dark humour emerges through exaggeration and accumulation, as ambition curdles into paralysis. The tragedy is not the futility of life, but that it installs an irrepressible desire to construct purpose, an urge that results in an all-consuming expansion of absurd theatre.

Black Swan — Darren Aronofsky (2010)

Black Swan frames perfection as a form of possession, where identity is sacrificed to an ideal that feeds on self-erasure. Here, artistic transcendence is inseparable from moral and psychic collapse. Mirrors, doubles, and bodily distortion suggest a split between the self that performs and the self that endures. The film deploys claustrophobic framing, invasive sound, and hallucinatory escalation, to lock the viewer inside a sentience devouring its own constructs. Any humour is cruel and fleeting, overwhelmed by the momentum toward annihilation. Virtuosity arrives at the point of destruction, once all demons have been released to feast, leaving a weightless, boundaryless void in their wake. The dance is no longer performed for validation of the ego, but declared as infinite emergence from darkness.

The Seventh Continent — Michael Haneke (1989)

Haneke’s first feature approaches annihilation with the cold clarity of an accounting ledger. The Seventh Continent presents modern life as a sequence of procedural gestures: repetitive, necessary, and utterly hollow. Alienation occurs through the slow erosion of significance via mechanistic routine. Austerity governs every choice: static framing, withheld emotion, and an almost punitive refusal of explanation, forcing the viewer into complicity through observation. There's no catharsis, no symbolic escape, only a terrifying, dispassionate logic. The material world is not merely insufficient, but actively hostile to spirit. When the conceit of purpose washes away, there's only one coherent response.

Luzifer — Peter Brunner (2021)

Luzifer situates belief at the edge of civilization, where isolation permits faith to evolve into something demonic. Brunner’s film is raw, allowing landscape, ritual, and bodily presence to dominate the frame. Nature offers no guidance, helping birth a distorted spirituality that mutates into fixation. Metaphysical tension surfaces in the struggle between imposed order and lived instinct, between doctrine and invention. Motherhood consists of an all-consuming love that manifests as abuse; the opposite motivation to nature's indifferent acceptance—an unwilled curse. A remote and oppressive seriousness permeates throughout, refusing relief. Meaning exists, but it's desperate and visceral, incapable of surviving intrusion. The result is a portrait of devotion stripped of transcendence, leaving only endurance, fear, and suffering in its wake.

Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself — Lone Scherfig (2002)

Scherfig’s gently eccentric film approaches despair with unexpected warmth, refusing false reassurance and embracing a comic nihilism. Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself treats suicidal ideation not as spectacle but as a persistent condition, woven into daily life. Comedy softens the tone, but existence remains painful, arbitrary, and resistant to resolution. The film’s modest realism allows small acts of care to carry disproportionate weight, highlighting kindness as a brief and exotic bloom in an otherwise cold world. There's a quiet irony in how connection arrives sideways, through responsibility and interruption rather than intention. Survival is provisional, sustained by moments that don't solve life, but make it briefly bearable.

I’ll See You in Disneyland — Thorkell A. Óttarsson (2022)

This enigmatic, low-budget indie, drifts between sincerity and estrangement. The surreal emerges as both refuge and deception. I’ll See You in Disneyland highlights the fragility of masculine self-worth when desire is spurned within a framework that values insensible dominance. Reality is found severely lacking, acting as a mirror to personal failure, and triggering violent lust. Instinctual longing retreats into archetypal imagination, with frequent uncertainty about whether unrestrained fantasy has burst through into the real world. In a cold culture of competition, the implicit danger applies to both the individual and collective unconscious. That is, when success is measured by basic biological function, and vulnerability and rejection mocked, a horrifying, archaic violence threatens to burst forth.

Burlesque (Az budou kràvy lita) — Tereza Kopáčová (2019)

Burlesque distils performance down to exposure, revealing how spectacle both empowers and consumes the body that sustains it. Kopáčová’s work is severe and intimate, embracing austerity as a way of stripping illusion from desire. Reality is exposed as superficially corporeal, and sexuality in the 'wrong' body, systemically rejected. Identity unfolds as something rehearsed, displayed, and gradually exhausted. There's titivation and humour, but it never distracts from the underlying vulnerability on display, and how it's punished by the community. The movie shatters the idea of human progress in a reactive world entrained to narrow fields of aesthetic legitimacy.

Menocchio, The Heretic — Alberto Fasulo (2018)

Menocchio, The Heretic is a film about repression and the battle to change a man's will. Specifically, the way the Catholic Church exacted is power through fear, surveillance, persecution, interrogation, torture, and death. However, heresies of all kinds are pursued in this way, including contemporary ones, although methods are usually more covert; digital algorithms policing and replacing cultural ones. For Menochhio, the freedom to speak a dire truth was sacred, and the false redemption of an imaginary god, the ultimate self-betrayal. Both lead to the death of the mortal soul, only one is a living death. It would be easy to swap in Winston, Orwell's protagonist from '1984'; Big Brother for God, the Church for the Ministry of Love, room 101 for the dark dungeon. Like Winston, Menochhio is broken by his rabid interlocutors. Despite being a popular character, and with many sympathizers for his views, the overarching message is clear: the program for basic biological survival, framed as pragmatism, overrides the truth whenever tyranny demands it. Honest men burn, and criminals take the throne.

Psalm 101 revisited

I will sing of your love and justice; to you, Big Brother, I will sing praise.

Psalm 101 re-revisited

I will sing of your love and justice; to you, The Economy, I will sing praise.